Strider V1/7 Scout Snipers in Hit, Iraq

Strider V1/7 Scout Snipers in Hit, Iraq

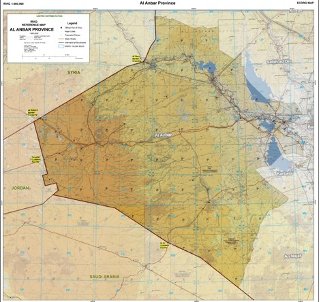

Patch of the First Team“My rifle and myself are the defenders of my country. We are the masters of our enemy. We are the saviors of my life”. This is the story of a group of men who embodied this excerpt from the Rifleman's Creed. They were and continue to be the very best of their generation. Whatever their reason for joining up and screening for the platoon, Americans should be grateful for their service and sacrifice. This is the story of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, or V17, call sign STRIDER, Scout Sniper Platoon that deployed during Operation Iraqi Freedom 6.8-2 to Al Anbar Province, Hit, Iraq (August 2007 through April 2008).

Patch of the First Team“My rifle and myself are the defenders of my country. We are the masters of our enemy. We are the saviors of my life”. This is the story of a group of men who embodied this excerpt from the Rifleman's Creed. They were and continue to be the very best of their generation. Whatever their reason for joining up and screening for the platoon, Americans should be grateful for their service and sacrifice. This is the story of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, or V17, call sign STRIDER, Scout Sniper Platoon that deployed during Operation Iraqi Freedom 6.8-2 to Al Anbar Province, Hit, Iraq (August 2007 through April 2008).

Reception, Staging, Onward Movement, and Integration The 28-member platoon was divided into four sections of eight teams, with one section serving as the Surveillance and Reconnaissance Center, or SARC Team, within the battalion Combat Operations Center, or COC. Each section had two school-trained Scout Snipers, commonly called “HOGs” (Hunter of Gunman), in charge of infantrymen who had attended a pre-sniper course and/or other advanced infantry training. The platoon had previously fallen under the leadership of the battalion's Weapons Company. However, for this deployment, the Battalion Commander, or BC, had shifted them under the Headquarters & Service Company, Intelligence Section (S-2) Officer-In-Charge.

The platoon had used the same call sign from Operation Iraqi Freedom One, or OIF I, until OIF VI, so it was an awkward initial platoon commander’s speech in that transient tent aboard Al Asad Airbase, directly adjacent to the Task Force Ripper, or 7th Marine Regiment compound before moving out to the battalion's Forward Operating Base, or FOB, north of Hit, Iraq. A Military Transition Team, or MiTT, had hijacked their beloved call sign RAVEN in between the battalion’s Iraq deployments. We initially conducted turnover with a 3d Infantry Division (also commonly referred to as the “Broken TVs”), Scout Platoon in Hit. They had scouts and snipers. Tactfully speaking, they were tired, and rightfully so. They had been extended to a 15-month deployment, coming down from Diwaniyah to Western Al Anbar Province.

The platoon had used the same call sign from Operation Iraqi Freedom One, or OIF I, until OIF VI, so it was an awkward initial platoon commander’s speech in that transient tent aboard Al Asad Airbase, directly adjacent to the Task Force Ripper, or 7th Marine Regiment compound before moving out to the battalion's Forward Operating Base, or FOB, north of Hit, Iraq. A Military Transition Team, or MiTT, had hijacked their beloved call sign RAVEN in between the battalion’s Iraq deployments. We initially conducted turnover with a 3d Infantry Division (also commonly referred to as the “Broken TVs”), Scout Platoon in Hit. They had scouts and snipers. Tactfully speaking, they were tired, and rightfully so. They had been extended to a 15-month deployment, coming down from Diwaniyah to Western Al Anbar Province.  The first joint patrol was educational. They had the M240G machinegun on point, and we were walking down the middle of a dirt road. I asked the "Army LT" what the deal was with the 240 on point without a sling. He explained they were punishing the young soldier for some past indiscretion. He told me not to worry, the soldier's sling had been replaced with a "550 cord”. That night, we set in our final firing positions on a peak overlooking a defunct Pepsi Cola factory after clearing a section of unoccupied old Iraqi Army fighting positions to provide overwatch on a small urban outcropping approximately 5 kilometers Southeast of the battalion FOB. Thankfully, that night would prove uneventful, and after a few hours of observation, we safely returned to base. From that point forward, the section and team leaders vowed to stamp out any complacency that may have been resident in the platoon.

The first joint patrol was educational. They had the M240G machinegun on point, and we were walking down the middle of a dirt road. I asked the "Army LT" what the deal was with the 240 on point without a sling. He explained they were punishing the young soldier for some past indiscretion. He told me not to worry, the soldier's sling had been replaced with a "550 cord”. That night, we set in our final firing positions on a peak overlooking a defunct Pepsi Cola factory after clearing a section of unoccupied old Iraqi Army fighting positions to provide overwatch on a small urban outcropping approximately 5 kilometers Southeast of the battalion FOB. Thankfully, that night would prove uneventful, and after a few hours of observation, we safely returned to base. From that point forward, the section and team leaders vowed to stamp out any complacency that may have been resident in the platoon.

Mission Sets By the time the platoon began operations in support of the battalion and distributed company positions in late 2007, the main terrorist group at the time, Al-Qaeda, had been militarily defeated. The Significant Event, or SIGACT, average was down to three incidents a day from six before January 2007 within what became the V17 Area of Operations, or AO. The platoon’s three main mission sets during the 7-month deployment were Counter-Sniper Operations, IED mitigation, and Building Partner Capacity (BPC), all in support of Multi-National Force- West’s Return to Normalcy campaign. In my professional judgment, the operational picture would have rapidly devolved if it weren't for the strong relationship between the battalion Operations and Intelligence Sections, and their respective leaders. There was much for the battalion to accomplish, ranging from Coalition Force Position Demilitarization, Targeted Raids, Detainee Operations, Key Leader Engagements, Military Source Operations, Civil-Military Operations, and building enduring strategic partnerships.

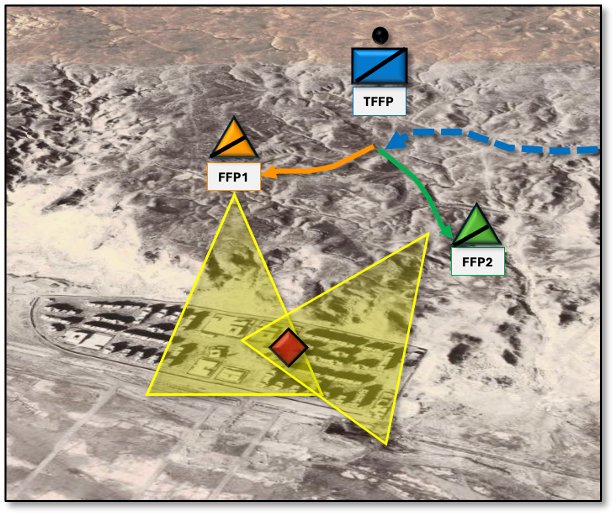

Due to the recent loss of a sniper team in Ramadi prior to our deployment, the minimum manning requirement to operate a reconnaissance mission was set at eight personnel by MNF-W. To better manage the sections’ physical signature, reduce the frequency of passive or active compromises, and increase their overall field of observation, the platoon employed a technique in which the sections split into two mutually supporting teams once they reached their Tentative Final Firing Position or TFFP.

Inside Our Counter-Sniper Mission The battalion AO was turned over to the four organic Marine Company Commanders (plus the attached Light Armored Reconnaissance Company from 3d LAR located East of the Euphrates River) from the 3d Infantry. Each Marine Captain became the de facto mayor of their respective AO. Most were hesitant to employ Scout Snipers in urban hides due to the perceived loss of local “Wasta” (Clout in Arabic) if a sniper team was passively compromised. This resulted in most companies not requesting sniper support from the battalion initially. This worked in the platoon's favor initially as they were afforded time to setup reactive target ranges on the FOB, run local reconnaissance patrols in the vicinity of the battalion FOB, and conduct battalion-level Reconnaissance and Surveillance, or R&S, to monitor the Main and Alternate Supply Routes, or MSR/ASRs. The combined S-2 and S-3 team, or S-5, as we referred to ourselves collectively, knew that counter-sniper operations were essential to our units in built-up urban areas based on the sordid history of the lower and middle Euphrates River Valley and adversary/ foreign fighter snipers.

The S-2 OIC was a staunch advocate of the sniper and special operations community – and a brilliant mind. He spent hours analyzing the most current imagery, then comparing it with recent SIGACT data, along with other intelligence information to determine where urban sniper operations would be most effective. To build trust with the local commanders, the battalion offered to conduct Threat Vulnerability Assessments, or TVAs at all Company and Platoon outposts as a Force Protection measure.  These TVAs were conducted by a composite grouping of the attached Human Intelligence Team and school-trained Scout Snipers from the platoon. The resulting assessments were well received, resulting in Company Commanders beginning to request Sniper Sections and Teams to co-locate at their positions for patrol integration, raid force initial terminal guidance, and force protection advisement. This ended up being a great pairing, complemented by our S-2 Marines leading the Company-Level Intelligence Cells (CLICs) prepositioned at the companies.

These TVAs were conducted by a composite grouping of the attached Human Intelligence Team and school-trained Scout Snipers from the platoon. The resulting assessments were well received, resulting in Company Commanders beginning to request Sniper Sections and Teams to co-locate at their positions for patrol integration, raid force initial terminal guidance, and force protection advisement. This ended up being a great pairing, complemented by our S-2 Marines leading the Company-Level Intelligence Cells (CLICs) prepositioned at the companies.

IED Mitigation: Neutralizing IED Threats in the Field Al-Qaeda may have been down, but they weren't out. The preferred weapon of our adversary during this deployment was IEDs. Although the majority were pressure plate IEDs, we also disrupted command-detonated IEDs. Luckily, the battalion was not taking substantial casualties at the time of our Relief in Place, or RIP. However, there were very real effects on theater logistics, trains, and general coalition force freedom of movement.  These missions would prove more complicated than perceived initially due to the advanced communications equipment (i.e., Tactical Chat, Satellite Communications, High Frequency) required to communicate voice and transmit near real-time images over vast distances, the deconfliction required with units transiting the AO to avoid fratricide, and creative logistical solutions needed to persist and sustain in a 115F+ desert environment for multiple periods of darkness, and finally the level of coordination required both internal to the battalion and with the supported companies to be viewed as an asset rather than a liability.

These missions would prove more complicated than perceived initially due to the advanced communications equipment (i.e., Tactical Chat, Satellite Communications, High Frequency) required to communicate voice and transmit near real-time images over vast distances, the deconfliction required with units transiting the AO to avoid fratricide, and creative logistical solutions needed to persist and sustain in a 115F+ desert environment for multiple periods of darkness, and finally the level of coordination required both internal to the battalion and with the supported companies to be viewed as an asset rather than a liability.

Despite the fielded counter-IED systems (i.e., minesweepers, electronic countermeasures, and rhino systems), the IED SIGACTs continued to hold firm at 2-3 per day. This average was not congruent with the MNF-W “Return to Normality”, and later “Transition to Provincial Iraqi Control” campaigns. The Intel section and the CLICs did their best to fuse and make sense of multi-source and multi-discipline intelligence information to drive future operations. To their credit, the information gathered by the battalion S-2, the company CLICs, and platoon-level fuelers underpinned the weekly battalion targeting boards, which underwrote the line companies’ platoon raids and subsequent detainee operations.

Certainly, the boys’ proficiency increased with all the extra work. However, it was hot. So hot that it became untenable to conduct persistent ground reconnaissance operations for more than 48 hours. The limiting factor was how much water the men could carry for sustainment. Initially, we conducted drops and caches of supplies that the teams could access under the cover of darkness. However, there were competing requirements for battalion lift assets. After all, the BC owned everything west of Ramadi and south of Haditha.

We knew that we had to hedge our bets to bring the average SIGACT count down so as not to impede operational and theater-level logistics, to build confidence in our partner force, and to gain the trust of the local population. The V17, or First Team, staff was all in on the problem set. Moreover, the companies were dialed in, the entire Task Force took the threat to the force and the mission personally, and they were willing to use all means necessary to neutralize it. A brilliant idea soon came from our Fire Support Coordinator, or FSO. This was for our S-2 Section to analyze not only where IEDs were emplaced and when they detonated, but also under what type of period of darkness. This type of analysis revealed that the majority of the IEDs were being emplaced on the MSRs (which were restricted to military convoys at the time) under cover of darkness with high illumination.

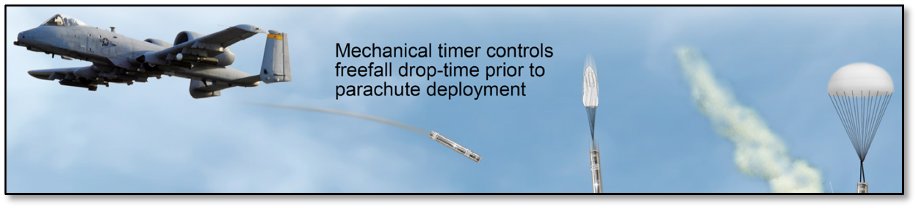

This changed our mindset from trying to set in only during low illum and begged the question: was canalization possible for adversary IED operations? And the corollary being, if so, then how? Again, our FSO came through with the idea to employ theater-level air assets to employ air-deployed LUU-2 high-intensity illumination flares. We consistently scheduled these air missions until we were notified by MNF-W that we had exhausted the theater reserve of this capability.

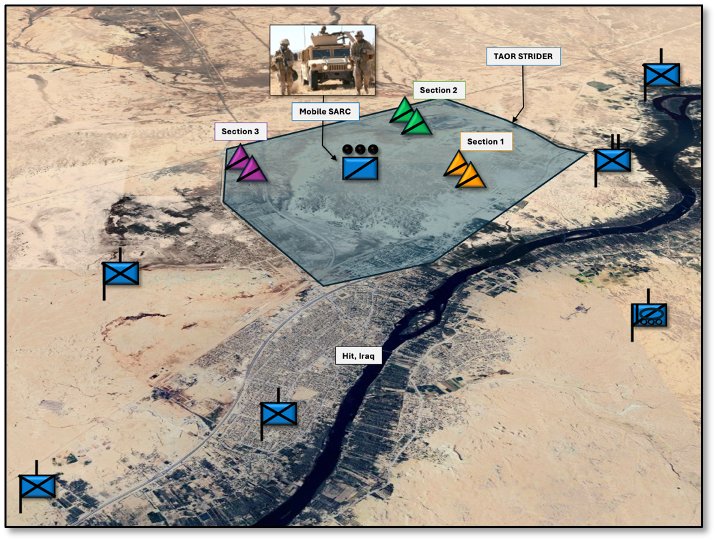

During this period, the average SIGACT count dropped to one per day, so we knew we were onto something. To reinforce success and seize momentum, the battalion Operations Officer proposed a platoon Tactical Area of Responsibility, or TOAR, instead of the BC approving individual sniper mission Concepts of Operations, or CONOPS.  So, a tactical concept to canalize the adversary in time and space, by concurrently employing a persistent maneuver unit in conjunction with several clandestine sniper teams to dictate operational tempo, was borne. The result was MNF-W approving an overarching TAOR STRIDER CONOPS for one-month. The basic scheme of maneuver was for the SARC to go mobile and generate area denial through a persistent overt presence while the entire platoon operated simultaneously in areas designated as IED "Hot Spots" by the S-2. The operation was commanded, controlled, and resupplied solely by the mobile SARC element. Although there were no direct adversary engagements, there were also no IED detonations for two months, starting before and after TAOR STRIDER concluded. This concept was only viable due to the dedication of the line and weapons companies, along with our attachments, the local MiTT, and our Iraqi counterparts. With the average SIGACT count reduced to .5 per day and no IED detonations, the platoon had additional capacity to advise and assist our Iraqi partners.

So, a tactical concept to canalize the adversary in time and space, by concurrently employing a persistent maneuver unit in conjunction with several clandestine sniper teams to dictate operational tempo, was borne. The result was MNF-W approving an overarching TAOR STRIDER CONOPS for one-month. The basic scheme of maneuver was for the SARC to go mobile and generate area denial through a persistent overt presence while the entire platoon operated simultaneously in areas designated as IED "Hot Spots" by the S-2. The operation was commanded, controlled, and resupplied solely by the mobile SARC element. Although there were no direct adversary engagements, there were also no IED detonations for two months, starting before and after TAOR STRIDER concluded. This concept was only viable due to the dedication of the line and weapons companies, along with our attachments, the local MiTT, and our Iraqi counterparts. With the average SIGACT count reduced to .5 per day and no IED detonations, the platoon had additional capacity to advise and assist our Iraqi partners.

Training Local Forces: Building Partner Capacity The boys had already been making cultural inroads with the 7th Iraqi Army (IA) Division soldiers stationed on the adjacent camp of FOB Hit when the Marine MiTT requested Sniper Training from STRIDER.  One of our snipers spoke Arabic and was a big hit with the "Jundee" (Iraqi Enlisted Soldiers). The request was initially denied by MNF-W leadership due to tradecraft concerns. However, the Chief Scout recommended general ground reconnaissance classes, followed by joint-combined reconnaissance patrols as a "practical application" or validation exercise. This idea was unanimously endorsed by MNF-W. With every successful joint-combined patrol completed, subsequent de-brief, and storyboard generated for Higher Headquarters consumption, the platoon's rock star status was elevated.

One of our snipers spoke Arabic and was a big hit with the "Jundee" (Iraqi Enlisted Soldiers). The request was initially denied by MNF-W leadership due to tradecraft concerns. However, the Chief Scout recommended general ground reconnaissance classes, followed by joint-combined reconnaissance patrols as a "practical application" or validation exercise. This idea was unanimously endorsed by MNF-W. With every successful joint-combined patrol completed, subsequent de-brief, and storyboard generated for Higher Headquarters consumption, the platoon's rock star status was elevated.

I can’t think of a time I feared for my life more than when on a patrol consisting of a squad of jundee, the Scout Sniper Platoon Commander, our Chief Scout, a few Marine Scouts, and of course, our Devil Doc. Conversely, I can’t think of a more purposeful time in which one group of professionals sought to imbue their knowledge and experience into another willing and worthy partner force fighting for their existence, while sharing risk and misery.

I can’t think of a time I feared for my life more than when on a patrol consisting of a squad of jundee, the Scout Sniper Platoon Commander, our Chief Scout, a few Marine Scouts, and of course, our Devil Doc. Conversely, I can’t think of a more purposeful time in which one group of professionals sought to imbue their knowledge and experience into another willing and worthy partner force fighting for their existence, while sharing risk and misery.

Saved Rounds & Alibis: Final Reflections from V1/7 I sincerely appreciate the opportunity to tell the platoon's story from the perspective of the platoon commander. The platoon’s reputation was such that by the winter of 2007, they were requested to conduct Regimental Level R&S to augment adjacent battalion operations near the Syrian border. The platoon would continue to acquit themselves as consummate professionals throughout the entire deployment. At the time of battalion redeployment, in early 2008, they had planned and executed more than 120 R&S missions with no serious injuries or casualties. I’m confident that the lion’s share of the platoon and battalion's success was directly attributable to the strong ties between the Operations and Intelligence Sections.

From this experience, I have continually advocated for all Marine Air Ground Task Forces to composite and train organic, all-weather ground reconnaissance capabilities to satisfy the commander's information requirements. When technology fails and the weather does not support friendly force operations, this skill set is essential to sensing and making sense across all operating environments. There are many complicated thoughts and memories associated with recounting the actions of these men. However, it is essential for both the previous generations of Scout Snipers and those that will embody the legacy of our Corps to know the story of these modern roughneck, ragged, adaptable, and brilliant precision shooters. There is no professional achievement that could ever top serving as the leader of these men and what's more, being educated by them and accepted as a fellow warrior.

Mike Masters

Former Platoon Commander

Scout Sniper Platoon, V17 “Strider”

Labels